Association BPSGM Les Basses Pyrénées dans la seconde guerre mondiale 64000 Pau

POLO BEYRIS: A FORGOTTEN FRENCH INTERNMENT CAMP, 1939-1947.

POLO BEYRIS. UN CAMP D’INTERNEMENT FRANÇAIS OUBLIÉ (1939-1947)

John Guse a accepté de nous communiquer le texte ci-dessous en vue de sa publication sur notre site. Nous l’en remercions vivement.

Notre site bpsgm.fr est heureux de pouvoir présenter ce texte en langue anglaise. C’est la première fois que nous proposons à nos lecteurs un article en anglais, mais ce ne sera pas la dernière. C’est pour nous une façon d’ouvrir notre site aux chercheurs anglo-saxons et, au-delà d’eux, à tous les anglophones.

Le camp de Beyris, construit en 1939 sur le terrain de polo à Bayonne, a été redécouvert il y a une dizaine d’années par un groupe de chercheurs historiens. Ce groupe a alors constitué le Collectif pour la mémoire du camp de Beyris à Bayonne, animé notamment par Claire Frossard, Michèle Degorce, Philippe Durut, Mixel Esteban, Claude Labat, Jean Riotte et, bien sûr, John Guse. Il a publié en 2013 Derrière les barbelés de Beyris, petit fascicule qui n’était pas passé inaperçu en Pays basque, tant le sujet avait sombré dans l’oubli. Son projet actuel est de publier l’année prochaine l’ouvrage de référence sur l’histoire du camp de Beyris, aux éditions Elkar (Bayonne). Nous attendons avec impatience la sortie de cet ouvrage.

Dr J. Guse est directeur émérite de l’American School of Paris. Il est actuellement inspecteur adjoint d’histoire et géographie pour l’option internationale du baccalauréat français. M. Guse est un Fulbright Scholar dont le principal domaine de recherche est la relation entre la technologie et l’idéologie dans le Troisième Reich.

Ses publications sont :

– « Nazi Technical Thought Revisited » in History and Technology, 2010

– « Volksgemeinschaft Engineers: The Nazi Voyages of Technology » in Central European History, 2011

– « Nazi Ideology and Engineers at War : Fritz Todt’s Speaker System » in Journal of Contemporary History, 2013

L’article publié ci-dessous est la première version faite par l’auteur de l’article qu’il avait publié en février 2018 dans le Journal of Contemporary History (JCH). Cette version diffère de la version publiée dans JCH, en ce qu’elle est dépourvue de certains arguments et précisions.

Le texte intégral peut être consulté (possibilité d’achat) sur le site

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0022009417712113

POLO BEYRIS: A FORGOTTEN FRENCH INTERNMENT CAMP, 1939-1947

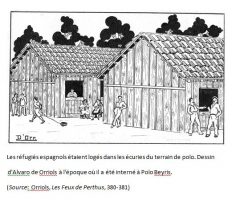

“Hunger for liberty, for work, for struggle, dreams of glory, poetic chimeras! …. All foundered on the hard reality of that shelter at Beyris.” When Spanish playwright Alvarro de Orriols wrote those words he could hardly have imagined that, years later, his memoirs would bring to light the ‘lost’ camp where he had been interned.[1] Orriols fled to France with the defeated Spanish Republicans in 1939, only to join his sister in a miserable refugee camp in Bayonne. He kept a hidden diary of his flight and internment which was published in Spain in 1995, twenty years after his death. Upon its translation into French in 2011, stupefied listeners at a book-reading in Bayonne first learned of a large ‘concentration camp’ in their city. In fact, the camp existed from 1939-1947, holding successively Spanish refugees, French colonial prisoners of war, collaborators and German prisoners of war. It was deliberately ‘forgotten’ in the political rush to extinguish memories of Vichy France and then quite literally erased, replaced with a 1960s housing project which left no trace of the camp. Although cited in local studies in the 1990s, the camp has received virtually no notice from historians of Vichy France until very recently, unlike the infamous nearby camp of Gurs. [2] For example, Denis Peschanki’s monumental La France des Camps makes no mention of Polo Beyris nor is it included in Julian Jackson’s list of camps in France: The Dark Years.[3]

In 2012, a group of local historians formed an association to shed light on the history of the ‘forgotten’ camp of Polo Beyris. Using local, departmental and national archives, the archives of the International Red Cross, and testimony from local residents, the association stitched together the history of Polo Beyris. The results have been a locally published brochure, several public conferences and a contribution to essays on exile and internment in the Lower Pyrenees.[4] Using their research as a starting point, this essay seeks to present a brief overview of the camp’s development, suggest its importance and encourage further research.

The story of the Polo Beyris camp is significant, not only because it fills a gap in the history of wartime France, but also because it is a study of the ‘camp experience’ under differing administrators. Historians have come to see the process of captivity – of refugees, political prisoners, ‘racial enemies’, prisoners of war – as key to the evolution of contemporary societies. The last century has been described as ‘the century of camps.’ [5] Although Polo Beyris has begun to find mention in studies of specific groups of captives – Spanish refugees or French or German prisoners of war – it is only by examining the totality of the camp’s evolution that we can respond to Denis Peschanski’s fundamental question regarding continuity within the camp experience. [6] At Polo Beyris, the difficult conditions in the camp varied little from its pre-war French administration, through German occupying forces to its post-war Liberation overseers.

Polo Beyris should be viewed in the context of the growing literature on internment in France prior to, during, and after World War II. Beyond the vast number of works on the fate of the Jews in France, numerous studies have broadened our understanding of how certain groups were treated and how captivity evolved. Prisoners of war, refugees, those considered ‘undesirable” or ‘dangerous’ by Vichy, suspected ‘collaborators’, all have been the subject of recent study.[7] Since the work of Anne Grynberg and Peschanski, studies of regional internment practices and individual camps have proliferated.[8] For the Southwest, the most significant case is Gurs, to which Claude Laharie drew attention already in the 1990s.[9] The camp of Polo Beyris provides further insight into how internment evolved in Southwestern France.

Laharie considers Gurs the focal point for administrative internment in the Southwest, with other camps functioning ‘in the shadow of Gurs’, often basically annexes to the large camp near Pau. He describes the camps of the Lower Pyrenees as chaotic environments, with the severity of confinement ranging from the repressive to permissive and where vastly differing groups were interned successively, and sometimes simultaneously, in the same camp: Spanish republicans, ‘undesirables’, foreign Jews, prisoners of war, collaborators – ‘The arrival of one followed closely on the departure of the others, as in a bad piece of theater.’ [10]

Much of this schema also fits Polo Beyris, but with considerable qualification. Bayonne was in a unique geographical situation: it was a major port with close maritime connections to Spain; it was close to the Spanish frontier; unlike Gurs, it was within the zone occupied by German forces, yet near the demarcation line; and furthermore it was within the so-called ‘Forbidden Zone’ (Zone Interdite), off limits to civilians from outside the zone. These factors meant that Polo Beyris and the surrounding area took on their own specific characteristics. The Basque coast served as a ‘funnel’ for returning Spanish refugees. During the German occupation, Bayonne and the Basque coast were tightly controlled, yet the proximity to the demarcation line and Spanish frontier afforded opportunities for escape. After the war, the camp’s location on the coast meant active use of German prisoners of war to clear the beaches and coast of mines and war materiel. All these factors made Polo Beyris unique and worthy of our attention.

It is important to note at this point what Polo Beyris was not: namely a camp whose prisoners were destined for deportation to Nazi concentration or death camps. Communists, foreign or French Jews and French Resistance fighters were detained in other local prisons or transferred immediately elsewhere. Foreign Jews, and some French Jews, arrested in round-ups in July and October 1942 were sent directly for imprisonment in Bordeaux prior to transfer to Drancy or to Auschwitz. Most remaining members of the long-established Jewish community in Bayonne were evacuated to the interior from the ‘forbidden’ coastal zone in May 1943, some were later arrested, others managed to be ‘forgotten’. [11] Polo Beyris was not a waystation in the Holocaust. As a consequence it has fallen outside the historiographical movement that has emphasized camps within the deportation process. Nor has it been memorialized in the same way as Gurs, Rivesaltes and other camps.

I- Spanish Refugees

In the early 1920s local and expatriate aristocrats, enamored of the sport of polo, established a polo club on the Basque coast. The Marquis de Jaucourt rented over eight hectares of land between Bayonne and Anglet and, together with fellow members of the French, Spanish and British nobility, created a large polo grounds with stables, changing rooms and a rudimentary clubhouse. Matches were held through the mid-1930s – the American Handicap Tournament in 1928, for example, pitted a team of continental nobles against a team of wealthy British officers – also including Americans, Argentinians and other South American aristocrats.[12] With the Great Depression and the advent of the Spanish Civil War, the polo club fell on difficult times. The number of players declined from 28 in 1935 to 8 in 1936, with many players returning to Spain, presumably to fight with Franco’s insurgents. [13] The owner of the polo ground property, Etienne Balsan, offered the grounds for sale and the Bayonne city council voted to purchase the property in February 1936 for the construction of a much-needed girl’s high school. The polo club played its final season at the Beyris site in Bayonne in 1937.[14] Thereafter the Spanish refugee crisis altered the city’s plans.

The Spanish Civil War had a profound impact on the southern provinces of France. After Republican defeats at Irun and Saint Sebastien in 1936, thousands of refugees arrived in southwestern France, probably around 15,000 in this period.[15] Representatives of the Popular Front government of Leon Blum, local authorities and many in the local population sought to ease the situation for refugee families. On the Basque coast ‘centers of assistance’ were established in Biarritz and Bayonne, popular events were held to raise funds, and the Bayonne newspaper Le Sud-Ouest ran a daily section in Spanish with news of the conflict. An abandoned military hospital in Bayonne was transformed into a refugee center, which by mid-October housed over 700 refugees, principally the aged, women and children.[16] By June 1937 the Bayonne center had 1150 refugees, with neighboring Basque communities joining in the effort.[17] Republican defeats in 1937-38 brought additional refugees. Even excluding the large numbers of Republican solders who returned to fight in Spain, there were an estimated 40,000 Spanish refugees on French soil at the end of 1938. [18] Faced with a growing number of refugees fleeing fascism – Jews, German opponents of Nazism, Austrians after the Anschluss – in addition to Spanish refugees, the government of Edouard Daladier adopted restrictive measures for foreigners, culminating in the infamous government decree of November 12, 1938, which provided that ‘undesirables’ be interned in ‘specialized centers’ and monitored as potential treats to public order and national security. This law served as a model for future internments when the war broke out.

The Spanish refugee crisis intensified dramatically between January 27 and February 12, 1939, when between 470,000 and 530,000 refugees flooded into France, the so-called retirada. An unprepared French government responded by fits and starts, initially allowing only women, children and the elderly to enter, then faced with an uncontrollable wave of fleeing soldiers, also accepting military refugees. ‘Concentration camps’ (a neutral term at the time) for disarmed Spanish troops were established on the beaches of Argelès-sur-Mer, Saint-Cyprien and Barcarès. In reality, these were not camps as such, but merely portions of beach delimited by barbed wire, holding over 200,000 troops – illustrated by Robert Capa’s famous photo of marching prisoners at Barcarès. To relieve the overcrowded beaches, the government created a system of internment camps, each with a capacity of approximately 20,000.[19] Women, children, the elderly, and some wounded Spanish troops were dispersed to ‘reception centers’ (centres d’accueils) throughout France. One of these destinations was Bayonne and its abandoned polo grounds.

On 6 February 6 1939, the mayor of Bayonne opened the stables and adjoining farm for Spanish refugees; two days later, the Sous-Préfet officially requisitioned Polo Beyris.[20] A public appeal was issued in the local newspaper requesting that families provide clothing for 600 children, most separated from their parents, being held there.[21] One witness recalls the ‘tired, miserable’ families arriving, lugging their belongings and pushing their carts through a cordon of police.[22] At the end of March the ‘reception center’ director reported 598 refugees at Polo Beyris: 43 elderly, 240 women, 278 children (it appears that many children had been dispersed to local orphanages) and 37 wounded Republican soldiers. This number declined as some refugees were transported to the camp at Gurs and others repatriated to Spain: in early September the center housed 440 refugees: 56 men, 183 women and 201 children. [23]

On 6 February 6 1939, the mayor of Bayonne opened the stables and adjoining farm for Spanish refugees; two days later, the Sous-Préfet officially requisitioned Polo Beyris.[20] A public appeal was issued in the local newspaper requesting that families provide clothing for 600 children, most separated from their parents, being held there.[21] One witness recalls the ‘tired, miserable’ families arriving, lugging their belongings and pushing their carts through a cordon of police.[22] At the end of March the ‘reception center’ director reported 598 refugees at Polo Beyris: 43 elderly, 240 women, 278 children (it appears that many children had been dispersed to local orphanages) and 37 wounded Republican soldiers. This number declined as some refugees were transported to the camp at Gurs and others repatriated to Spain: in early September the center housed 440 refugees: 56 men, 183 women and 201 children. [23]

The camp consisted of five rows of unheated buildings, surrounded by fence or high bramble hedges and guarded by French gendarmes. The refugees were housed in exceedingly primitive conditions, the majority in former stables, with only the upper half of a Dutch door to serve as a window in daylight hours. There was no furniture, with straw on the floor, an army blanket to serve as a bed and the stable manger to store whatever few belongings the refugees might own. Many suffered from the cold. A fortunate few were housed in the former changing rooms of the polo club, which meant a building with a door, windows, and eventually some rudimentary furniture. The camp contained an eating hall and a large washhouse, which served both as a water source and for washing clothes. Meals were an unvarying diet of rice, pasta and lentils; nurses made occasional visits to administer cod liver oil to children. The refugee detainees were forbidden to leave the camp or to seek work.[24] Evidence suggests that able bodied men were quickly transferred to the detention camp at Gurs.

Throughout 1939, the French government, intent on maintaining good relations with Franco’s successful nationalists and faced with a public opinion increasingly hostile to a flood of poor, ‘red’ refugees, sought by various means to repatriate as many refugees as possible. Already by February 19, 50,000 had chosen to return, most via Hendaye, the only port of entry to Nationalist Spain. This made the Basque coast, with its camp at Polo Beyris, the center of repatriation activity. Many refugees refused to return, however, unaware of the whereabouts of loved ones or fearful of the danger of returning to Franco’s Spain. The repatriation process was also slowed as the government recognized the potential economic and military value of keeping relatively skilled refugees, especially with the declaration of war in September and consequent loss of manpower due to conscription. Able bodied men were recruited for agricultural and industrial labor; the Compagnies de travailleurs étrangers were used for labor by the army, and Spanish exiles were enrolled in the Foreign Legion.[25]

With the coming of the war the ‘reception centers’, and to a degree, the detention camps, were quickly emptied. The remaining refugees of Polo Beyris were forcibly evicted at the end of September 1939, a scene that one witness recalls as ‘horrible’: crying infants, screaming mothers pulled by their hair as they were loaded onto wagons for transport to the frontier.[26] On October 2 the Préfet of the Lower Pyrenees stated that the center had been ‘completely evacuated’, with the last 260 refugees destined for Spain and an additional 16 sent to Gurs.[27]

II- French Colonial Prisoners of War

The camp would not remain empty long. With the French military defeat in June 1940, German troops entered Bayonne, in the coastal occupied zone of southwestern France, on June 27. Two months later the German military authorities requisitioned the buildings and grounds of Polo Beyris for a prisoner of war camp, Frontstalag 222. This was but one of an initial fifty-seven prisoner camps created in occupied France by the Germans in 1940 to hold captured French colonial troops.[28] Raffael Scheck, Armelle Mabon, Martin Thomas and others have recently described in detail the fate of colonial troops at the hands of the Germans, including the abuse and massacre of black prisoners during the 1940 campaign and the conditions of their subsequent imprisonment.[29] Based on both French and German sources, Scheck estimates that there were 90,000 – 100, 000 colonial troops in captivity in the summer of 1940, and still at least 86,000 in March 1941, with a rapid decline thereafter, due primarily to the release of soldiers for illness and for German propaganda purposes. By March 1942, 40,000 colonial troops remained in captivity, a number that declined only slowly thereafter.[30]

In the wake of the French defeat, the Germans initially moved colonial soldiers — with other French troops — to prisoner of war camps in Germany, only to return most of the colonial troops to camps in France after September.[31] Nazi racist propaganda, combined with memories of French colonial troops occupying the Rhineland in the 1920’s, called the ‘black shame’ in Germany, fed fear of racial ‘contagion’ – not to mention real contagion by tropical disease.[32] In addition, the Vichy government reinforced the notion that colonial troops, unaccustomed to the rigorous northern European climate, were risks for tuberculosis and should be repatriated.[33] The colonial troops that arrived in Bayonne were among those that had been held in captivity in Germany. A convoy of two trains carrying 1300 colonial prisoners took two days to reach Laharie, north of Bayonne, during which more than 180 escaped.[34] They were dispersed to the Frontstalags in the region; on November 14 over 800 prisoners arrived at Polo Beyris.[35]

In the wake of the French defeat, the Germans initially moved colonial soldiers — with other French troops — to prisoner of war camps in Germany, only to return most of the colonial troops to camps in France after September.[31] Nazi racist propaganda, combined with memories of French colonial troops occupying the Rhineland in the 1920’s, called the ‘black shame’ in Germany, fed fear of racial ‘contagion’ – not to mention real contagion by tropical disease.[32] In addition, the Vichy government reinforced the notion that colonial troops, unaccustomed to the rigorous northern European climate, were risks for tuberculosis and should be repatriated.[33] The colonial troops that arrived in Bayonne were among those that had been held in captivity in Germany. A convoy of two trains carrying 1300 colonial prisoners took two days to reach Laharie, north of Bayonne, during which more than 180 escaped.[34] They were dispersed to the Frontstalags in the region; on November 14 over 800 prisoners arrived at Polo Beyris.[35]

The Germans, assisted by the city’s engineers, had hastily constructed a major internment camp on the Polo Beyris site, designed to house 5000 – 6000 prisoners.[36] The camp covered nearly nine hectares of land with 55 wooden barracks, four washhouses, ten toilet structures, ten barracks/offices for the guards and an administrative center in the polo clubhouse. The camp was surrounded by three concentric barbed wire fences and guarded by five wooden guard towers.[37] The camp commander, Major Beste, lived in a large nearby villa.[38] Most of the guards were older soldiers, veterans of World War I, members of the ill trained Landesschützen battalions created in September 1940 to guard the Frontstalags. Evidence suggests that, as elsewhere, these guards treated the prisoners humanely.[39]

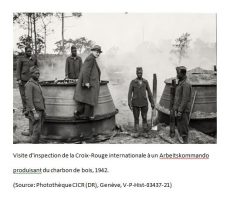

Beginning with 800 internees in October 1940, the camp grew quickly. To prevent overcrowding and to make use of prisoner labor, the German military authorities established ‘satellite’ camps (Arbeitskommandos) in the surrounding area, particularly in the pine forests north of Bayonne, where the prisoners were engaged in cutting trees and manufacturing charcoal.[40] The constant movement between labor camps makes it difficult to determine with precision the total numbers of prisoners at a given time.[41] In the summer of 1941, the main camp and its four principal sub-camps (Messanges, Buglose, Labenne and Hendaye) contained approximately 2500 prisoners, with an additional 200 hospitalized.[42] The Red Cross counted 1100 prisoners at the main Polo Beyris camp in June 1941, but only 482, occupying only 15 barracks, in October 1942.[43] This figure demonstrates the dispersion of prisoners to the growing number of satellite work camps rather than any significant reduction in prisoners, as the Scapini Mission reported 3600 prisoners in October 1941– the camp having tripled in size in three months.[44] In mid-1943 the main Frontstalags in the south-west were consolidated. Thus by January 1944, in the midst of frenetic construction of the Atlantic defenses by the Organization Todt, when colonial prisoners were used primarily for wood production in the forests, Frontstalag 222 counted 20 separate work camps, in addition to the main Polo Beyris camp, with a total of 6804 prisoners.[45] This appears to have been the largest number of prisoners during the war. On 8 March 1944, Frontstalag 222 became Dulag 222 (Durchgangslager, that is transit camp), evidence of the use of Polo Beyris as a distribution center, including for the eventual liberation of prisoners.[46] The total number of prisoners declined to 5684 by July 31, 1944, three weeks before the liberation of the camp.[47]

Beginning with 800 internees in October 1940, the camp grew quickly. To prevent overcrowding and to make use of prisoner labor, the German military authorities established ‘satellite’ camps (Arbeitskommandos) in the surrounding area, particularly in the pine forests north of Bayonne, where the prisoners were engaged in cutting trees and manufacturing charcoal.[40] The constant movement between labor camps makes it difficult to determine with precision the total numbers of prisoners at a given time.[41] In the summer of 1941, the main camp and its four principal sub-camps (Messanges, Buglose, Labenne and Hendaye) contained approximately 2500 prisoners, with an additional 200 hospitalized.[42] The Red Cross counted 1100 prisoners at the main Polo Beyris camp in June 1941, but only 482, occupying only 15 barracks, in October 1942.[43] This figure demonstrates the dispersion of prisoners to the growing number of satellite work camps rather than any significant reduction in prisoners, as the Scapini Mission reported 3600 prisoners in October 1941– the camp having tripled in size in three months.[44] In mid-1943 the main Frontstalags in the south-west were consolidated. Thus by January 1944, in the midst of frenetic construction of the Atlantic defenses by the Organization Todt, when colonial prisoners were used primarily for wood production in the forests, Frontstalag 222 counted 20 separate work camps, in addition to the main Polo Beyris camp, with a total of 6804 prisoners.[45] This appears to have been the largest number of prisoners during the war. On 8 March 1944, Frontstalag 222 became Dulag 222 (Durchgangslager, that is transit camp), evidence of the use of Polo Beyris as a distribution center, including for the eventual liberation of prisoners.[46] The total number of prisoners declined to 5684 by July 31, 1944, three weeks before the liberation of the camp.[47]

The prisoners at Polo Beyris came from all parts of the French empire, but the majority was from North Africa. In July 1941, the Scapini Mission reported that 56% of a total of 2425 prisoners at Polo Beyris and its four principal sub-camps were North African, of whom the large majority (65%) was Algerian. Nearly 40% were ‘Senegalese’, a category that included natives of all French Sub-Saharan colonies, not just Senegal.[48] Others were from Madagascar (102), Martinique (18) and French Indo-China (4). The demographic dominance of North African prisoners held true through the consolidation of various Frontstalags and dispersion of labor camps during the war. In January 1944, North Africans made up 67% of the prisoner population, however more evenly distributed between Algerians (47%), Moroccans (36%) and Tunisians (17%).[49]

What is particularly striking in the statistics of Polo Beyris and its dependent camps during its early period is that it was almost exclusively the Sub-Saharan prisoners that were sent to the labor camps, whereas the North Africans were confined to the main camp. For example, in July 1941 all of the various satellite labor camp prisoners were black (‘Senegalese’, Malgaches or Martiniquais), with the exception of a group of 400 Moroccans at one camp, whereas 93% of the main camp population was North African.[50] Several factors may account for this practice: German anti-colonial propaganda sought to attract North African prisoners to the Axis cause, thus perhaps easing their workload; the Germans sought to reduce tensions between North African and black prisoners by dispersing most of the latter to satellite camps; and the Germans probably assumed that easily recognizable black prisoners were less likely to escape.[51] As the camp grew and consolidated with others, and its satellite labor camps multiplied, the distribution of workers by ethnic grouping shifted significantly. A greater percentage of North Africans were used in the dispersed labor camps, although when this change took place is uncertain. By January 1944, the main camp held only 674 prisoners, 81% being Moroccan, but its twenty labor camps had 6030 prisoners, 35% Algerians, 17% Moroccans, 13% Tunisians, and only 26% ‘Senegalese’.[52] This reflected both the German need for labor in the forests to support Atlantic Wall construction and the imperative of preventing overcrowding in the main camp.

Tensions between ethnic groups of prisoners at Polo Beyris erupted frequently, often linked to accusations of corruption, as was the case in many other Frontstalags.[53] These included disputes between North African and Sub-Saharan or other black colonial troops, but also within these groups. Algerian prisoners at Polo Beyris resented Moroccan prisoners, who often received parcels from Morocco, while the Algerian government neglected them.[54] Tribal-based disputes arose between black soldiers, particularly in the satellite camps of Labenne and Saint Menard. The so-called ‘man of confidence’, who represented the prisoners to the camp authorities and to visiting inspectors, could be a source of internal camp tensions. In 1944 an Algerian ‘man-of-confidence’ at Polo Beyris was accused of charging fifty francs to each new internee and of embezzling mutton to sell to the Muslim prisoners at Ramadan.[55]

Conditions in the main camp were rudimentary, but livable. Red Cross reports say that initially the food supply was sufficient (one report calls them ‘excellent’), particularly when augmented by Red Cross deliveries of supplemental supplies.[56] Unfortunately, the German authorities prohibited such deliveries from the unoccupied zone in October 1941, because, as Rafael Scheck explains, they discovered that Red Cross drivers had smuggled letters, messages and escaped prisoners across the demarcation line. Thereafter, the food supplies of the Frontstalags in the Southwest were the worst in France, and the prisoners suffered accordingly.[57] Fortunately for the prisoners, the local population participated to a limited degree to improve the situation. Sunday dinners were prepared by volunteers, donations of vegetables were collected at local markets, bread was surreptitiously smuggled to prisoners. The food supply was worse in the isolated satellite camps which had been heavily dependent on Red Cross deliveries. However, in some cases prisoners could use their meager pay to purchase food locally or were able to eat a Sunday dinner with a local family, as was common at satellite camps in Bidache, Labenne and Morcenx.[58] Witnesses in Labenne remember locals exchanging food for cigarettes from the prisoners and camp authorities allowing individual prisoners, accompanied by a guard, to spend time with local families.[59]

Conditions in the main camp were rudimentary, but livable. Red Cross reports say that initially the food supply was sufficient (one report calls them ‘excellent’), particularly when augmented by Red Cross deliveries of supplemental supplies.[56] Unfortunately, the German authorities prohibited such deliveries from the unoccupied zone in October 1941, because, as Rafael Scheck explains, they discovered that Red Cross drivers had smuggled letters, messages and escaped prisoners across the demarcation line. Thereafter, the food supplies of the Frontstalags in the Southwest were the worst in France, and the prisoners suffered accordingly.[57] Fortunately for the prisoners, the local population participated to a limited degree to improve the situation. Sunday dinners were prepared by volunteers, donations of vegetables were collected at local markets, bread was surreptitiously smuggled to prisoners. The food supply was worse in the isolated satellite camps which had been heavily dependent on Red Cross deliveries. However, in some cases prisoners could use their meager pay to purchase food locally or were able to eat a Sunday dinner with a local family, as was common at satellite camps in Bidache, Labenne and Morcenx.[58] Witnesses in Labenne remember locals exchanging food for cigarettes from the prisoners and camp authorities allowing individual prisoners, accompanied by a guard, to spend time with local families.[59]

Such practice reinforces the impression that prisoners from Polo Beyris, like many other Frontstalag throughout France, benefitted from active assistance among the French population. Rafael Scheck goes so far as to argue that colonial prisoners were better treated by the population at large than by fellow prisoners in the camps.[60] The so-called ‘godmothers’ of prisoners of war, an officially sanctioned program, often adopted a local colonial prisoner as their ‘godchild’. Amical relations developed among prisoners and local residents, especially on the farms scattered far from the strict control of the main camp. This could lead to sexual and romantic relationships, as attested to by post-war marriages between ex-prisoners and locals.[61]

Such practice reinforces the impression that prisoners from Polo Beyris, like many other Frontstalag throughout France, benefitted from active assistance among the French population. Rafael Scheck goes so far as to argue that colonial prisoners were better treated by the population at large than by fellow prisoners in the camps.[60] The so-called ‘godmothers’ of prisoners of war, an officially sanctioned program, often adopted a local colonial prisoner as their ‘godchild’. Amical relations developed among prisoners and local residents, especially on the farms scattered far from the strict control of the main camp. This could lead to sexual and romantic relationships, as attested to by post-war marriages between ex-prisoners and locals.[61]

According to testimony from residents around Polo Beyris, locals provided well organized assistance for escaping prisoners. This ranged from smuggling in wire cutters (hidden inside baked bread) to providing food to those who escaped through the camp sewer system to transporting escapees across the demarcation line and to Spain in vegetable carts, under piles of industrial laundry, even in empty caskets. The white eyes of an escaped ‘black’ staring out of the dark bushes behind his house still haunt the childhood memories of one witness; another provided clothes to an ‘Arab’ escapee who burst into the shop where he worked; he then threw the soldier’s uniform in the river.[62] Evidence suggests that such escape attempts were relatively common.[63] This, again, points to the uniqueness of Polo Beyris and its satellite camps: their proximity to the demarcation line and the Spanish frontier facilitated such actions.

Of course not all escapes were successful, and guards did not hesitate to shoot prisoners attempting to escape: in October 1942 the Red Cross reported two ‘Senegalese’ had been shot attempting to escape from a local satellite camp.[64] Far and away the greatest cause of death, however, was disease, especially tuberculosis. A total of 150 prisoners died of disease in the camp’s infirmary and hospitals, with 1941 being the deadliest year, accounting for a third of the deaths. [65] This total may be low, however, because some ill prisoners were evacuated to the ‘free’ zone where they were cared for by the Vichy authorities, often in poor hospitals. It is difficult to determine how many of their deaths can be directly attributed to camp conditions.[66]

Dulag 222 was liberated on 22 August 1944, amid considerable confusion. Prisoners scattered throughout the area, some returning to the farms or local businesses that employed them during the occupation, others were housed by local residents or in hastily created shelters. On August 31 an announcement in the locally printed newspaper, La Résistance Républicaine, ordered all former prisoners to report to the military barracks in Bayonne or face charges of desertion. A photograph of a Liberation celebration in September shows a delegation of ‘Senegalese’, former prisoners, among the participants.[67] Some prisoners became guards at their former camp when it was converted to hold German prisoners of war.

Raffael Scheck argues that the experience of colonial prisoners in German captivity in France was different from, but no worse than, that of other ‘white’ prisoners and Western POW’s in Germany.[68] Although they should be treated with skepticism, reports of the Red Cross inspectors in June 1941 and October 1942 describe Polo Beyris as a camp ‘perfectly well organized’, with clean, vermin-free barracks, and sufficient food and clothing — when the supplements provided regularly by the Red Cross were included. The October report concludes that Polo Beyris was ‘one of the best camps visited’.[69] The camp commander, Major Beste, was praised for his humane treatment of the prisoners.[70] Evidence suggests that living and working conditions in the main Polo Beyris camp were no more harsh, and food shortages notwithstanding, probably less so, than in the other Frontstalags throughout France.

III- Suspected Collaborators

Hardly had the last German troops evacuated Bayonne, when the camp of Polo Beyris was commandeered on 18 September 1944, as a detention center for those accused of collaboration with the enemy, beginning the third phase of its existence. By order of the new Sous-Préfet or the Comité Départemental de Liberation, some individuals were taken directly to the camp. Others had been ‘arrested’ on the street or in their homes by the Free French forces and interned in local prisons in Bayonne and Biarritz prior to their transfer to Polo Beyris.[71] On September 19, sixteen convoys arrived at the camp from the Bayonne prisons with 171 prisoners, 110 men and 61 women.[72] Desperate to halt the anarchic series of arrests, the Sous-Préfet ordered on September 20 that no further arrests could take place without his permission.[73] Thus Polo Beyris, like other camps, contributed to what Denis Peschanski calls ‘social regulation’, creating an official and legal framework for the épuration.[74] It is important to note here that the épuration sauvage on the Basque coast was less intense than in many other parts of France. Little evidence exists of spontaneous killings of collaborators or of the public humiliation of women.[75] Reasons for this include the tight German control of the coast, where the French Resistance had been less active than in the interior, and, as Claude Laharie has shown, the Milice in the Lower Pyrenees engaged in few actions likely to spark vengeance at the Liberation.[76]

Accusations against those arrested included direct collaboration with the Germans, including ‘intimate collaboration’, joining the Milice or the Légion des volontaires français (LVF), denouncing another French citizen, participating in the black market, or being a member of a collaborationist political party (Parti Populaire Français [PPF] or Rassemblement National Populaire [RNP]). A detailed analysis of the files for 600 individuals arrested between 21 August 1944, and 7 April 1945 (the majority before November 1944), is revealing.[77] Most accusations were for ‘political/patriotic’ reasons, namely direct collaboration with the Germans, denunciation or for being a member of a collaborationist party. Only 16% were specifically for black market involvement. The breakdown is as follows:

Reason for arrest: Men Women Total % Total

Relation with a German 6 13 19 3,16 %

‘collaboration intime’ 24 24 4 %

Economic delinquency 80 14 94 15,66 %

Collaboration 117 40 157 26,16 %

Milice 29 4 33 5,5 %

links to Gestapo 4 4 0,06 %

LVF 10 10 1,66 %

Collaborationist party member

PPF 89 23 112 18,66 %

RNP 11 3 14 2,33 %

Denunciation 30 29 59 9,83 %

Smuggling 4 4 0,06 %

Worked in Germany 1 1 0, 016 %

Diverse (propaganda, etc.) 51 18 69 11,5 %

Total: 600

On November 28 the commandant of Polo Beyris, now officially referred to as a ‘concentration camp,’ indicated that a large number of internees were not aware of why they had been arrested and were demanding their interrogation. A group of seven women wrote to the Préfet, saying they had been arrested in August by unidentified individuals (‘without armbands’), imprisoned in Biarritz for five weeks and brought to Polo Beyris without any indication of the motive for their arrest. Not until February 1945 did the Préfet come to the camp for ‘triage’ of prisoners according to the seriousness of accusations against them – which produced ‘an excellent impression’! That month 22 prisoners were transferred to Gurs, 69 liberated and 14 placed under house arrest. [78]

Commissions to Verify Internments (CVI) were created, beginning their work at the end of October 1944. The decisions taken by the Commission to Verify Internments were often contradictory and not always based on information in the interrogation reports furnished to them. Analysis of the cases of 720 arrested individuals nevertheless reveals a pattern in the punishments decided. Over a quarter of those arrested were liberated, and half of them without their case even going before a CVI – often by order of the Comité de Liberation or Sous-Préfet, who were pressured to free well-connected persons or individuals considered vital to the local economy. Those freed by the CVI itself had been either falsely accused, were without proof of guilt, or had been forced to work for the Organisation Todt. Those arrested for belonging to collaborationist parties usually were sent before the Civic Chamber and stripped of their civic rights, while those accused of economic collaboration ended up before the Committee for the Confiscation of Illicit Profits. Those accused of serious collaboration (Gestapo connections, Milice, denunciations) – some forty individuals, 5.5% of the total – were sent before the criminal Court of Justice. Others were simply imprisoned for a period ranging from two months to five years or placed under house arrest.[79] In this way, the CVI dispensed a rough and often arbitrary justice, slowly reducing the number imprisoned at Polo Beyris.

Despite the fact that there were far fewer accused collaborators than there had been colonial prisoners of war, the rudimentary conditions in the camp changed little. Part of the camp was subdivided into barracks for men and for women. Detainees slept on beds with straw or simple mattresses and two ‘coverlets’; they were allowed to use their personal bedcovers with the onset of winter. The camp, with barbed wire fencing and five watchtowers, was under French administrative authority with a military administration – although, a sign of the chaotic times, the Minister of the Interior was still uncertain in late December if the camp was under the authority of the Préfet, or if it was controlled by the FFI. [80] Colonial troops were used as guards – some were former prisoners there – and an additional contingent of twenty Francs-tireurs et partisans (FTP) patrolled the exterior of the camp. A doctor was assigned to the camp by the Sous-Préfet, assisted by two doctors, a dentist and two nurses, all of whom were prisoners in the camp.[81] At least one prisoner was shot, in this case for repeatedly attempting to pass a letter to someone in the women’s barracks.[82] Camp records indicate at least six escapes, two of whom were recaptured.[83]

As might be expected at a time of acute food shortages in France, the major difficulty facing the prisoners was hunger. The camp was dependent on the city of Bayonne for food, but local inhabitants also lacked food. Regulations set the ration for an adult prisoner at a meager 350 grams of bread daily, 250 grams meat per week, and monthly supplements dominated by potatoes.[84] In March 1945 dehydrated vegetables were introduced, apparently to good effect, as fresh vegetables were lacking.[85] Overall, conditions in the camp were very primitive, marked by lack of food.

Precise records in the departmental archives provide figures on the size of this ‘concentration camp.’ The camp commandant indicated on 27 October 1944, that the camp held 391 prisoners (278 men and 113 women).[86] A month later he reported 468 prisoners: 431 French (289 men and 142 women) plus 37 foreigners – and said the camp could hold up to 2500 prisoners. In January the Préfet repeated this figure and claimed that the camp could last for ‘a number of years’! [87] In mid-January 1945 the camp had 396 prisoners; at the end of March there were still 198 prisoners in the camp. These figures, however, do not take into account the constant movement of prisoners: some arriving, some liberated, some transferred to other prisons or to Gurs. By the end of January 1945, 789 prisoners had entered the camp, of whom 181 had been liberated and 68 transferred to Gurs.[88] Thus it appears that at least 800 accused individuals passed through the gates of Polo Beyris.[89] On April 20, 1945, the last of the accused were liberated, placed under house arrest or transferred to Gurs, freeing barrack space for German prisoners of war arriving from Gurs the same day.[90]

IV- German Prisoners of War

In November 1944 Polo Beyris embarked on its last phase as a detention camp, namely for German prisoners of war. The first German POWs, extremely young recruits, arrived that month, joined in January 1945 by 310 older troops who had been captured in August 1944 and previously held at Gurs.[91] Polo Beyris, which still had suspected collaborators when the German troops arrived, was divided into two parts, with a separate enclosed section created for the German prisoners.[92] When the camp was emptied of the last suspected collaborators, it was devoted entirely to German POW’s and was re-christened Dépôt 189. It was one of the many camps for German prisoners described in detail by Fabien Théofilakis, and the only one on the south Atlantic coast.[93] The youngest prisoners, many under age 17, were later transferred to Dépôt 183 at St. Médard en Jalles, near Bordeaux, where they were engaged as agricultural laborers. One contingent of former SS troops was particularly badly treated — housed separately, poorly fed, kept without shoes.[94] The camp was under the authority of the French military administration (18eme Region Militaire). As had been the case with the German military administration of Frontstalag 222, Dépôt 189 quickly created a multitude of satellite labor camps, both to ease the strain on an overcrowded main camp and to meet the acute labor shortage in a country recovering and rebuilding after occupation and war.

In November 1944 Polo Beyris embarked on its last phase as a detention camp, namely for German prisoners of war. The first German POWs, extremely young recruits, arrived that month, joined in January 1945 by 310 older troops who had been captured in August 1944 and previously held at Gurs.[91] Polo Beyris, which still had suspected collaborators when the German troops arrived, was divided into two parts, with a separate enclosed section created for the German prisoners.[92] When the camp was emptied of the last suspected collaborators, it was devoted entirely to German POW’s and was re-christened Dépôt 189. It was one of the many camps for German prisoners described in detail by Fabien Théofilakis, and the only one on the south Atlantic coast.[93] The youngest prisoners, many under age 17, were later transferred to Dépôt 183 at St. Médard en Jalles, near Bordeaux, where they were engaged as agricultural laborers. One contingent of former SS troops was particularly badly treated — housed separately, poorly fed, kept without shoes.[94] The camp was under the authority of the French military administration (18eme Region Militaire). As had been the case with the German military administration of Frontstalag 222, Dépôt 189 quickly created a multitude of satellite labor camps, both to ease the strain on an overcrowded main camp and to meet the acute labor shortage in a country recovering and rebuilding after occupation and war.

The camp grew dramatically in size, although the actual number of prisoners at the main camp varied considerably dependent upon successive arrivals and departures. The main camp functioned primarily as a holding area prior to newly arrived prisoners being assigned to work detachments. From 90 prisoners in February it grew to 3071 prisoners in the main and satellite camps by 5 May 1945. That day 468 wounded German soldiers arrived at the Bayonne train station, only to be greeted by an angry crowd who molested several of them. Days later, 1992 additional prisoners arrived from Strasbourg, including very young soldiers from FLAK units, ages 14-18, and members of the ‘Tartar Legion’; this time they were protected by the police and gendarmerie. By February 1946 the camp held over 5000 German and Austrian prisoners, with 925 present at the main camp. In June 1946 the camp attained its largest number, with 8600 prisoners, 4000 in the main camp, including 1500 newly arrived prisoners from the United States. Thereafter, the process of demobilizing German POWs accelerated rapidly: a little over two months later, on 26 August 1946 there were only 3500 prisoners. Nevertheless, in March 1947, five months prior to the last prisoners being released, the camp still held 3222 POWs, 245 in the main Polo Beyris camp.[95]

The prisoners were dispatched to satellite labor camps (many the same as those used for French prisoners of war) and to the multitude of smaller work detachments that were created to carry out specific tasks. The Secours Quaker counted 132 such labor detachments in 1945 (with 68% of the camp’s prisoners) and 150 five months later (with 77% of the prisoners).[96] Prisoners were made to clean and repair war damage and, most dangerously, to clear the beaches, dunes and cliffs of German mines. Horst Fusshöller, a twenty-year-old prisoner, explains in his memoirs that his motivation for volunteering to clear mines was “hunger and the will to survive”, despite the fact that supplemental rations for taking the risk amounted to only 350 calories per day.[97] Prisoners in the mine clearing details were often housed in primitive conditions in the abandoned bunkers and barracks on or near the beaches. Fusshöller recounts that “the worst for us was sleeping directly on the concrete floors.”[98] Throughout France at least 5000 prisoners were injured or died in de-mining operations, figures which are probably vastly underestimated.[99]

The prisoners were dispatched to satellite labor camps (many the same as those used for French prisoners of war) and to the multitude of smaller work detachments that were created to carry out specific tasks. The Secours Quaker counted 132 such labor detachments in 1945 (with 68% of the camp’s prisoners) and 150 five months later (with 77% of the prisoners).[96] Prisoners were made to clean and repair war damage and, most dangerously, to clear the beaches, dunes and cliffs of German mines. Horst Fusshöller, a twenty-year-old prisoner, explains in his memoirs that his motivation for volunteering to clear mines was “hunger and the will to survive”, despite the fact that supplemental rations for taking the risk amounted to only 350 calories per day.[97] Prisoners in the mine clearing details were often housed in primitive conditions in the abandoned bunkers and barracks on or near the beaches. Fusshöller recounts that “the worst for us was sleeping directly on the concrete floors.”[98] Throughout France at least 5000 prisoners were injured or died in de-mining operations, figures which are probably vastly underestimated.[99]

Prisoners were also set to work on reconstruction projects. In the summer of 1945 the Minister of the Interior urged local communities to use the prisoners of war as labor: “They destroyed it….They should repair it! Rebuild your ruins….Beautify your cities…make the enemy prisoners work.”[100] Local communities often used the prisoners for road reconstruction. Prisoners were also hired by private firms, including local farmers, for agricultural labor, in the forests of the Landes and in enterprises facing a labor shortage. Indeed, as Fabien Theofilakis has shown, the labor of prisoners of war became such a crucial element in post-war reconstruction that France deliberately delayed releasing German prisoners for months despite the urging of the other Allies.[101]

Treatment of hired prisoners varied enormously, ranging from ‘deplorable’ on one work commando in August 1947, with prisoners housed in a makeshift shed on dirt floors, to situations like that of Emil M., who appreciated the ‘humanity’ of his carpentry boss and, like some others, opted to continue working for him as a Free Civil Worker after his release.[102] Communities or private employers were enjoined by the French military authorities to follow strict regulations for the prisoners, with all mail censured and clothing clearly marked with a ‘P.G.’ (prisonnier de guerre); employers considered ‘lax’ for allowing prisoners too much freedom were reprimanded.[103] At Polo Beyris, discipline was labeled ‘very severe’, particularly after ‘Senegalese’ recruits took over as guards in the spring of 1946. A doctor attempting to escape was beaten by the guards, leading to a protest among the prisoners — who did not accept being beaten by a black. Another escape by a doctor led to confinement of all German doctors in the evening.[104]

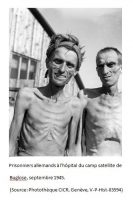

By far the major difficulty faced by the prisoners was insufficient food, a recurring problem at a time of significant food shortages for the whole population. In July 1945 the International Red Cross described the camp rations as ‘clearly insufficient’ and prisoners ‘in a state of extreme gauntness.’ The prisoners were being fed an inadequate quantity of cabbage and turnip soup. A year later the inspectors reported that the prisoners were supposedly receiving 1500 calories per day, but that they could not carry out hard labor because of their insufficient rations, especially those on de-mining operations. Prisoners, even when ill, sought to be on the work details of the Americans in Biarritz, clearing the beach and cleaning gardens, because the American military authorities fed them more than others. Numerous cases of cachexia and edema deficiency were reported, particularly given that many prisoners were already malnourished before arriving at Dépôt 189. For example, in early February 1945, all 22 prisoners arriving from Gurs suffered from edema deficiency.[105]

Rations at the main camp improved somewhat over time : tomatoes, salads and radishes were planted in 1946 and a ‘well stocked’ mess was created where working prisoners could afford to buy lemonade, beer and articles from the American military stocks; by March 1947, the Red Cross considered the food supply satisfactory at 2300 calories per day.[106] However, the vast majority of prisoners were not in the main camp, but dispersed in the satellite camps and labor detachments where supplementary food supplies were haphazard or nonexistent. Photos taken of malnourished prisoners in the hospital at Buglose, north of Bayonne, show emaciated bodies reminiscent of Nazi concentration camp survivors.[107] Nor could German prisoners, unlike their French colonial counterparts, expect significant support for the local population. Indeed, the Red Cross reported in May 1945 that their local representatives, who sought to provide fruits and vegetables to the prisoners, ‘encountered difficulty in carrying out their action.’[108]

In addition to a shortage of food, the German prisoners suffered from a serious lack of adequate clothing. Most had arrived at Polo Beyris with only the uniform on their back, having lost or discarded their military coats during their numerous transfers. “The prisoners nearly all have no shoes,” reported the Red Cross in February 1945. In November 1945 the camp commander managed to obtain 2000 pairs of wooden soles, but it was only in March 1947 that the camp received 3000 pairs of shoes from the German army. Some clothing was furnished by the Red Cross, and American uniforms were distributed when the American base in Biarritz closed in June 1946, but prisoners still lacked underwear, shirts and socks.

In addition to a shortage of food, the German prisoners suffered from a serious lack of adequate clothing. Most had arrived at Polo Beyris with only the uniform on their back, having lost or discarded their military coats during their numerous transfers. “The prisoners nearly all have no shoes,” reported the Red Cross in February 1945. In November 1945 the camp commander managed to obtain 2000 pairs of wooden soles, but it was only in March 1947 that the camp received 3000 pairs of shoes from the German army. Some clothing was furnished by the Red Cross, and American uniforms were distributed when the American base in Biarritz closed in June 1946, but prisoners still lacked underwear, shirts and socks.

Inadequate clothing compounded the difficult sleeping conditions. In November 1945, 250 prisoners had no bed and were sleeping on straw, while half of the ill prisoners in the infirmary had no coat to use as a cover and were suffering greatly from the cold. Wood was often missing for the wood-burning stoves used to heat the barracks. [109] The main camp systematically lacked straw for mattresses, with many prisoners sleeping directly on wooden bunks with only a blanket – with not enough blankets for all prisoners. And the conditions in the satellite camps and work detachments were usually worse than in the main camp. In his beachside bunker Horst Fussholler recounts that, with the coming of winter, “we were all frozen.”[110] Prisoners systematically suffered from lice and fleas. The camp was treated with DDT, but prisoners returning from work commandos often re-infected the camp; prisoners detached to the Americans in Biarritz underwent daily delousing there, but would return the following day again with lice.[111]

The combination of insufficient nourishment and lack of adequate clothing worsened the medical situation. Many prisoners arrived at the camp in a malnourished condition, weakened by time spent in unsheltered conditions and after long transfers. Others had been wounded. The internal camp hospital at Polo Beyris plus a requisitioned military hospital in Bayonne became gathering points for the sick and wounded, as the German prisoners could not be treated in civilian hospitals. At the end of October 1945 the camp infirmary held 679 sick prisoners (18% of the camp internees), 200 of whom suffered from edema caused by hunger and 130 recovering from enteritis. In February 1946 the infirmary still had 182 ill prisoners, including 16 too weak to work and 44 surgical cases, 16 from de-mining accidents.[112] Between February 1945 and September 1946, 85 German prisoners of war at Polo Beyris died, two-thirds prior to November 1945.[113] Of the differing groups interned at Polo Beyris between 1939 and 1947, it seems clear that the conditions for the German prisoners were the worst.

Conclusion

The history of Polo Beyris after 1947 is one of long, complex negotiations between the city of Bayonne and the French state over reparations for use of the land during the war and recuperation of the space for the city. Already in November 1944 the mayor of Bayonne sought payment for lost revenue, claiming that the area could have been used by the city for market gardening. By April 1946 the city had given up on its pre-war project for a girls’ school in favor of a plan to use the grounds as a cemetery, while also agreeing to rent the space to the French army – it was the German POW camp at the time – for a limited period. After the camp was emptied of German prisoners, the city sought to recuperate the camp and its barracks, with a view to house poor families, due to the post-war housing shortage. In early 1948 it was determined that the camp barracks were unusable for housing – leaking roofs, dangerous electrical connections, generally unhealthy conditions – and the camp remained abandoned.[114] In July 1949 the mayor began negotiations with the Ministry of Reconstruction, seeking financial aid for ‘the removal of all the last remains of the installation constructed during the occupation.’ Now the city envisioned that the ‘vast plateau’ of Polo Beyris would become ‘a residential quartier covered with beautiful homes’ and hence ‘all traces of the occupation must disappear.’ [115] Politics had caught up with the city’s planning: the mayor’s statement was a clear expression of the desire of French authorities at the time to wipe away all references to ‘the dark years’ of the German occupation. The negotiations and subsequent land clearance took ten years. In June 1960, when the first cornerstone was laid for what would become a residential area of apartment buildings, individual homes and a school, the mayor of Bayonne made no reference whatsoever in his remarks to the camp or to the many prisoners it had held.[116] At a time of Franco-German rapprochement, when the less said about French or German prisoners of war the better, Polo Beyris had already been deliberately forgotten.

To fully describe Polo Beyris – prisoners, guards, administration, interactions with the local population, comparisons to other camps – requires more space and further research in French and German archives. Nevertheless, we can learn some lessons from our brief history of Polo Beyris. It was a major camp, until now virtually unknown, with as many as 600 Spanish refugees, 6000 French colonial prisoners of war, 470 suspected collaborators or 8600 German prisoners of war at a given moment. It bears resemblance to many such camps elsewhere: hastily commandeered or constructed housing created under crisis circumstances; rudimentary, at times squalid, living conditions; a constant movement of prisoners in and out of the camp; discipline that varied widely in its intensity; chronic food shortages. These factors demonstrate continuity of the camp experience over time and apply to both the administrative and military control of the camp.

We can, however, draw distinctions between the periods of internment. The worst housing was for Spanish refugees, in windowless stables with straw bedding — more a sign of the improvised nature of the camp than of a voluntary desire to demean the refugees. The German prisoners suffered the most, lacking adequate clothing and sufficient nourishment to carry out their often dangerous labor. French colonial prisoners of war fared better. This was due to a certain military rigor on the part of a German camp administration within occupied France and to limited humanitarian assistance from the local population. In reality, for those imprisoned at Polo Beyris, German military internment was preferable to French military internment. Suspected collaborators, under administrative supervision, were relatively the best off.

On the spectrum of twentieth century camps, the conditions at Polo Beyris were obviously far from the unimaginable horror of Nazi death camps or the Soviet Gulag. Nevertheless, Polo Beyris is yet another example of how political authorities, both democratic and authoritarian, willingly imprisoned those who they considered a threat to the social fabric or callously made use of prisoners of war. As at Gurs, refugees, suspected collaborators, prisoners of war found themselves behind the same barbed wire, in similarly wretched conditions. Their well-being and survival was dependent on the ability and willingness of camp authorities to provide satisfactory food, clothing and medical aid – an aleatory proposition. Their suffering was quickly forgotten both by political authorities seeking to erase an unpleasant past and a population willing to do so.

[1] Alvaro de Orriols, Les Feux du Perthus (Toulouse 2011), 391.The left-leaning de Orriols, who wrote a play for the Spanish exhibit at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair, had been condemned to death by Franco.

[2] André Plouzeau, ‘Troupes coloniales en captivité dans les Basses-Pyrénées’, Cahier n° 1 de l’Association Mémoire Collective en Béarn, (Pau, 1995); André Pintat, ‘Le Frontstalag 222 du Polo Beyris à Bayonne,’ Revue d’Histoire de Bayonne 154 (1999), 403-410; Louis Poullenot, Basses-Pyrénées. Occupation. Libération. 1940-1945 (Biarritz, 1995).

[3] Denis Peschanski, La France des camps. L’Internement, 1938-1946 (Paris 2002); Julian Jackson, France: The Dark Years, 1940-1944 (Oxford 2001), 633-635. Peschanski shows a camp incorrectly labeled ‘Le Pole’ on a map of camps., 460.

[4] Collectif pour la mémoire du camp de Beyris, Derrière les barbelés de Beyris, published by the Ville de Bayonne, June 2013; Laurent Jalabert (ed.), Exodes, Exils et Internements dans les Basses-Pyrénées 1936-1945 (Pau 2014). Forthcoming : a fuller history of the camp, Ekkar editions, 2019.

[5] Joël Kotek and Pierre Rigoulot, Le siècle des camps (Paris, 2000). See also Marc Bernardot, Camps d’étrangers (Bellecombe-en-Bauges 2008) and on migrant camps Alain Rey, Parler des camps au XXIe siècle (Paris 2015).

[6] Peschanski, La France des Camps, 17, 475.

[7] Notably: Raffael Scheck, French Colonial Soldiers in German Captivity during World War II (New York 2014); Armelle Mabon, Prisonniers de guerre ‘indigènes’: Visages oubliés de la France occupée (Paris 2010); Fabien Théofilakis, Les prisonniers de guerre allemands : France, 1944-1949 (Paris 2014); Laurent Duguet, Incarcérer les collaborateurs – Dans les camps de la Libération, 1944-1945 (Paris 2015).

[8] Anne Grynberg, Les Camps de la honte: les internés juifs des camps français, 1939-1944 (Paris 1991). Among others : Peter Gaida, Camps de travail sous Vichy ( Raleigh, NC 2014); Teresa Ferre and Manuel Guerrero, Agusti Centelles – Le Camp de Concentration de Bram 1939 (Barcelona 2009); Eric Malo and Denis Peschanski, Le Camp de Noé: 1941-1947 (Pau 2009); Jean-Yves Boursier, Un camp d’internement vichyste: Le sanatorium surveillé de La Guiche (Paris 2004); Jean-Marc Dreyfus and Sarah Gensburger, Des camps dans Paris: Austerlitz, Lévitan, Bessano (Paris 2003). Earlier discussion of camps in Southwest France in Monique-Lise Cohen and Eric Malo (eds), Les Camps du Sud-Ouest de la France: Exclusion, internement et déportation, 1939-1944 (Toulouse 1994).

[9] On Gurs, Claude Laharie, Le camp de Gurs (1939-1945). Un aspect méconnu de l’histoire de Vichy (Biarritz 1991); Claude Laharie, Gurs. L’art derrière les barbelés (1939-1944) (Biarritz 2008); Martine Chéniaux and Joseph Miqueu, Le Camp de Gurs (1939-1945). Un ensemble de témoignages (Pau 2011); Ernst O. Bräunche and Jurgen Schuhladen, Briefe-Gurs-Lettres: Briefe einer badisch-jüdischen Familie aus französichen Internierungslagern ( Karlsruhe 2011); Joël Kotek and Didier Pasamonik, Mickey à Gurs: Les carnets de dessin de Horst Rosenthal (Paris 2014). Early attention was drawn to Gurs by Hanna Schram and Barbara Vormeier, Vivre à Gurs ( Paris 1979).

[10] Claude Laharie, ‘Les camps des Basses-Pyrénées pendant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale (1939-1945): les différentes formes de l’enfermement,’ in Jalabert, Exodes, 43-63. Laharie argues that this lack of organization was due to the stubborn slowness of the French administration to catch up with political change and to the improvisational nature of these internments.

[11] Mixel Esteban, ‘Les Juifs du Pays basque. De l’exclusion de la citoyenneté à la « solution finale »’ in Laurent Jalabert, Exodes, 92-96.

[12] Edouard Labrune, Côte Basque des Années Folles (Urrugne 2015), 46-47.

[13] Letter of the Société Hippique et Polo de Biarritz, 16 November 1936, Archives départementales des Pyrénées-Atlantiques – Bayonne [hereafter ADPA-Bayonne], E dépôt Biarritz 3 R 59.

[14] City council minutes, February 3, 1936, ADPA-Bayonne, E dépôt Bayonne 1 D 54 and letter of Count Guy de Bourg de Bozas, May 7, 1937, ADPA-Bayonne, E dépôt 3 R 59. The polo club president lobbied the mayor of neighboring Biarritz to construct a new polo field there, where with “the return of prosperity” the club would “contribute to the elegance” of the city. Letter of Count Guy de Bourg de Bozas to the mayor of Biarritz, 24 September 1936, ADPA-Bayonne, E dépôt 3 R 59.

[15] Geneviève Dreyfus-Armand, L’exil des républicains espagnols en France. De la guerre civile à la mort de Franco (Paris 1999), 34.

[16] Le Sud Ouest Républicain, early 1937, and La Presse du Sud-Ouest, 20 October 1936, Médiathèque de Bayonne.

[17] Guethary, with 300 women and children; Bidart, 100 children; Hendaye, 160 refugees . 10 June 1937, Centres d’hébergement de réfugiés espagnols, Archives départementales des Pyrénées-Atlantiques-Pau [hereafter ADPA-Pau], 4 M 254 Police.

[18] José Cubero, ‘L’accueil des républicains espagnols dans le piémont pyrénéen’ in Jalabert, Exodes, 24. Among the many studies of Spanish exiles : Dreyfus-Armand, L’Exil des républicains espagnols en France; José Jornet et.al., Républicains espagnols en Midi-Pyrénées : Exil, histoire et mémoire (Toulouse 2005) and Davila Valdes Claudia, Les réfugiés espagnols de la Guerre Civile en France et au Mexique: Histoire comparée des politiques d’asile et des processus d’intégration (Sarrebruck 2010).

[19] Cubero, ‘L’accueil des républicains espagnols,’ 26.

[20] Order of Sous-Préfet de Bayonne, 8 February 1939, ADPA-PAU, 4 M 254.

[21] Sud-Ouest Républicain, 15 February 1939, Médiathèque de Bayonne. This is the first indication of the number of refugees in the camp.

[22] Testimony of Georges Darridol, Collectif, Derrière les barbelés, 9.

[23] Reports of camp director, 25 March and 5 September 1939, ADPA-Pau, 4 M 244.

[24] Alvaro de Orriols, Les feux du Perthus, 378-379, 393; testimony of Mercedes de Orriols, Collectif, Derrière les barbelés, 13-15.

[25] Cubero, ‘L’accueil des républicains espagnols,’ 32-41. Cubero provides a detailed description of public attitudes toward the refugees, the repatriation process and the economic and military use of refugees. He estimates that the number of Spanish exiles who remained to engage in various ways for the French Republic numbered 200,000 by the end of 1939.

[26] Testimony of Pablo Biel Maro, age 12 at the time and also interned at Polo Beyris, Collectif, Derrières les barbelés, 11.

[27] Letter of the Préfet des Basses Pyrénées to the Minister of the Interior, 2 October 1939, ADPA-Pau, 4 M 244.

[28] The number of Frontstalags was reduced by consolidation. In 1941 there were 22 Frontstalags; by April 1942 these had been further reduced to eight main camps, including Polo Beyris, and their associated satellite labor camps.

[29] Raffael Scheck, Hitler’s African Victims: The German Army Massacres of Black French Soldiers in 1940 (New York 2006); Scheck, French Colonial Soldiers; Armelle Mabon, Prisonniers de guerre ‘indigènes’; Martin Thomas, ‘The Vichy Government and French Colonial Prisoners of War, 1940-1944,’ French Historical Studies 25, nr.4 (2002).

[30] Scheck, French Colonial Soldiers, 27-29.

[31] From 2,000 – 3,000 colonial troops remained in Stalags in Germany. Ibid, 29.

[32] Dick van Galen Last and Ralf Futselaar, Black Shame: African Soldiers in Europe, 1914-1922 (London 2015).

[33] Mabon, Prisonniers ‘Indigènes’, 32

[34] André Plouzeau includes a detailed account of the trip left by the doctor accompanying the troops. Plouzeau, ‘Troupes coloniales’, annex B, 20-21.

[35] Four days later, on the occasion of a visit of Marshal Pétain’s wife to the camp, a newspaper account states that there were 812 prisoners and another 230 at a camp in Hendaye. Le Petit Parisien, November 18, 1940, Médiathèque de Bayonne.

[36] Letter of mayor of Bayonne, 1 October 1940, ADPA-Bayonne, 1 W 14.

[37] Description and map of the camp in ADPA-Bayonne, 22 W 1.

[38] Testimony of caretaker’s family, Collectif, Derrière les barbelés, 20.

[39] Raffael Scheck provides extensive evidence of humane treatment by guards throughout the Frontstaglags. Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 91- 98.

[40] The Vichy government accepted the use of prisoners for labor as part of its collaboration policy. Raffael Scheck, ‘The Prisoner of War Question and the Beginnings of Collaboration: The Franco-German Agreement of 16 November 1940,’ Journal of Contemporary History 45, nr. 2 (2010), 383. On the satellite camps, see François Campa, Les prisonniers de guerre coloniaux dans les Frontstalags landais et leurs Kommandos, 1940-1944 (Bordeaux 2013).

[41] Only partial statistics are contained in Red Cross inspection reports of October 1942 and November 1943. Inspections of the Scapini Mission in April, July and October 1941 provide additional figures, but further research is required. (Georges Scapini was charged by Petain to negotiate with the Germans concerning French prisoners of war; after France replaced the United States as the ‘protecting power’ for French POW’s in November 1940, Scapini’s office regularly inspected Frontstalags in occupied France.)

[42] The 11 June 1941 visit of the Red Cross indicates 2566 total prisoners at Polo Beyris (1100) and its sub-camps at Messanges (190), Bugloze (700), Labenne (500)and Hendaye (76), with an additional 230 hospitalized in Bayonne (including ill from Frontstalag 195). International Committee of the Red Cross Archives , Geneva. [This and all following references to Red Cross inspections of Frontstalag 222 are from ACICR, C SC, France, Frontstalags, RT.] These figures match quite closely with the visit of the Scapini Mission on 7-9 July 1941, which show 2425 prisoners attached to Frontstalag 222: Polo Beyris (1101), Messanges (183), Bugloze (598), Labenne (475) and Hendaye (68). Service historique de la Défense-Vincennes [hereafter SHD-Vincennes], 2 P 78 Frontstalag.

[43] Red Cross inspection visit, 11 June 1941.

[44] Scapini Mission inspection of 17 October 1941, Archives Nationales-Pierrefitte [hereafter AN-Pierrefitte], F 9, 2356, cited in Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 111n.

[45] The main camp contained only 674 prisoners at the time. An additional 186 were hospitalized and 50 were imprisoned in Bayonne. Sous-direction du Service des Prisonniers de Guerre, Centre de Bordeaux, 31 January 1944. AN-Pierrefitte, F/9/2959.

[46] Correspondence from Bundesmilitärarchiv – Freiburg.

[47] Sous-direction du Service des Prisonniers de Guerre, Centre de Bordeaux, 31 July 1944. AN–Pierrefitte, F/9/2959.

[48] Mission Scapini inspection of 7-9 July 1941, SHD Vincennes, 2 P 78 Frontstalag. The cemetery of Bayonne St-Leon has graves of deceased prisoners from Dahomay, Sudan, the Ivory Coast and Guinée, in addition to Senegal. Partial list in André Plouzeau, ‘Troupes Coloniales,’ 24-26.

[49] Effectifs des Frontstalags, 31 January 1944, Sous-Direction du SPG, Centre de Bordeaux, AN–Pierrefitte, F/9/2959.

[50] Mission Scapini inspection of 7-9 July 1941, SHD Vincennes, 2 P 78 Frontstalag. Rafael Scheck considers this situation uncommon. Correspondence with the author, 22 September 2016.

[51] On German propaganda aimed at prisoners, Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 132-156; Mabon, Prisonniers ‘indigènes’, 153-168.

[52] Effectif des Frontstalags, 32 January 1944, Sous-direction du SPG, AN-Pierrefitte, F/9/2959.

[53] On inter-camp tensions, Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 219-228.

[54] Red Cross inspection visit of 11 June 1941.

[55] Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 223, 225.

[56] Red Cross inspection visits of 11 June and 29 October 1942.

[57] Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 193.

[58] Collectif, Derrière les barbelés, 29; Plouzeau, ‘Troupes coloniales,’ 16.

[59] One prisoner hauled his drunk guard back to camp! Testimony of Colette Magieu and Pierre Dutrey, Collectif, Derrière les barbelés, 30.

[60] Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 239.

[61] Collectif, Derrière les barbelés, 29. On amorous relations between prisoners and civilians see Mabon, Prisonniers ‘indigènes,’ 94-96; Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 235-239.

[62] Testimony of Michel Menta, Fernande Leb and other local residents, Collectif, Derrière des barbelés, 32-33. On French Resistance aid to escaping prisoners, Armelle Mabon, ‘Solidarité nationale et captivité coloniale’, French Colonial History 12 (2011), 193-207. Descriptions of various escape attempts throughout France and Résistance involvement in Mabon, Prisonniers ‘indigènes’, 115-126.

[63] Despite Red Cross reports (visits of 28-29 October 1942) of ‘a very small number’ of escape attempts from a satellite camp and none from the main camp, evidence suggests otherwise. At Mont-de-Marsan so many escapes occurred that the mayor forbade civilian contact with the prisoners. ‘Le frontstalag 222 de Bayonne,’ Cahier n° 1 de l’AMCB, 30, cited in Mabon, Prisonniers ‘indigènes’, 120. See the statistics on escapes in Campa, Les prisonniers de guerre coloniaux, 46-49.

[64] Red Cross inspection visit of 28 October 1942. Armelle Mabon cites a 1941 report that German guards throughout France were killing three prisoners per week, representing 5-7% of escape attempts. Mabon, Prisonniers ‘indigènes’, 120.

[65] Red Cross inspection of lazaret, 29 October 1942. Forty-eight prisoners were buried in Anglet and their remains later transferred to the military memorial at Chasseneuil sur Bonnieure, 102 others are interred in a Bayonne cemetery. The average age of those who died was thirty, the youngest was twenty, the oldest forty-four.

[66] Raffael Scheck correspondence with the author, 22 September 2016.

[67] Collection Aubert, Musée de Bayonne.

[68] Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 10.

[69] Red Cross inspection visits of 11 June 1941 and 29 October 1942.

[70] Scheck, French Colonial Prisoners, 111.

[71] Report of camp commandant, 20 November 1944, Centre d’accueil et de recherche des Archives Nationales, Paris [hereafter CARAN-Paris], F/7/15104. Prisons included the so-called ‘Maison Blanche’ in Biarritz, the municipal prison in Bayonne (the ‘Villa Chagrin’) and the Château Neuf in Bayonne.

[72] Report of camp commandant, 20 September 1944, ADPA-Pau, 72 W 123.

[73] Order of Sous-Préfet de Bayonne, 20 September 1944, ADPA-Pau, 72 W 118.

[74] Peschanski, La France des Camps, 443.

[75] Statistics on humiliation of women in Fabrice Virgili, France ‘virile’: Des femmes tondues à la libération (Paris 2004)

[76] Claude Laharie, ‘La Milice des Basses-Pyrénées (1943-1944). Un bref aperçu,’ in Laurent Jalabert and Stéphane Le Bras, eds., Vichy et la collaboration dans les Basses-Pyrénées (Pau 2015), 109-129. Sandra Ott’s groundbreaking anthropological study of the Basque region of Xiberoa shows the divisiveness of the Liberation there: War, Judgement and Memory in the Basque Borderlands (Reno 2008). See also her recent Living with the Enemy: German Occupation, Collaboration and Justice in the Western Pyrenees, 1940-1948 (Cambridge 2017).

[77] Records of the commissariat central de Bayonne, ADPA- Bayonne, series 1001 W, folios 306-318, 319-327, 333.

[78]. Report of camp commander, 28 November 1944, CARAN-Paris, F/7/15104; letter in ADPA-Bayonne, 1001 W 308; monthly report for February, 14 March 1945, CARAN-Paris, F/7/15104.

[79] Thanks to Claire Frossard for her analysis of these cases, all found in records of the commissariat central de Bayonne, ADPA- Bayonne, 1001 W 306-318, 319-327, 333.

[80] Minister of the Interior to Préfet, 22 December 1944, CARAN-Paris, F/7/15104.

[81] Report of camp commandant, 28 November 1944, CARAN-Paris, F/7/15104.

[82] Report of Renseignements généraux, Hendaye, 30 November 1944, ADPA–Pau, 1031 W 181.

[83] Summary report, 13 February 1945, ADPA-Pau, 72 W 123.[This report is incorrectly labeled as pertaining only to January 1945.]